Another Name For Large Intestine

| Big Intestine | |

|---|---|

Forepart of abdomen, showing surface markings for the liver (red), and the tum and large intestine (bluish). The large intestine is like an upside downwards U. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Alimentary canal |

| Organisation | Digestive organisation |

| Avenue | Superior mesenteric, junior mesenteric and iliac arteries |

| Vein | Superior and inferior mesenteric vein |

| Lymph | Junior mesenteric lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Colon or intestinum crassum |

| MeSH | D007420 |

| TA98 | A05.vii.01.001 |

| TA2 | 2963 |

| FMA | 7201 |

| Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] | |

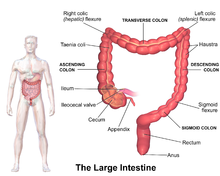

The big intestine, too known as the large bowel, is the terminal part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste matter is stored in the rectum every bit feces before being removed by defecation.[1] The colon is the longest portion of the big intestine, and the terms are often used interchangeably just nigh sources define the large intestine equally the combination of the cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal.[1] [two] [iii] Some other sources exclude the anal culvert.[4] [5] [6]

In humans, the big intestine begins in the right iliac region of the pelvis, just at or below the waist, where it is joined to the finish of the small intestine at the cecum, via the ileocecal valve. Information technology and so continues as the colon ascending the abdomen, across the width of the abdominal cavity as the transverse colon, and then descending to the rectum and its endpoint at the anal canal.[7] Overall, in humans, the large intestine is about 1.5 metres (5 ft) long, which is nearly one-fifth of the whole length of the human alimentary canal.[eight]

Structure [edit]

Illustration of the large intestine.

The colon of the big intestine is the terminal role of the digestive organization. Information technology has a segmented appearance due to a series of saccules called haustra.[ix] It extracts water and salt from solid wastes before they are eliminated from the body and is the site in which the fermentation of unabsorbed material past the gut microbiota occurs. Unlike the small intestine, the colon does not play a major function in assimilation of foods and nutrients. Nearly i.v litres or 45 ounces of water arrives in the colon each day.[ten]

The colon is the longest part of the large intestine and its average length in the adult human being is 65 inches or 166 cm (range of 80 to 313 cm) for males, and 61 inches or 155 cm (range of 80 to 214 cm) for females.[xi]

Sections [edit]

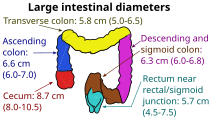

Inner diameters of colon sections

In mammals, the large intestine consists of the cecum (including the appendix), colon (the longest function), rectum, and anal canal.[i]

The four sections of the colon are: the ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. These sections turn at the colic flexures.

The pats of the colon are either intraperitoneal or behind it in the retroperitoneum. Retroperitoneal organs, in general, do not have a consummate roofing of peritoneum, then they are fixed in location. Intraperitoneal organs are completely surrounded past peritoneum and are therefore mobile.[12] Of the colon, the ascending colon, descending colon and rectum are retroperitoneal, while the cecum, appendix, transverse colon and sigmoid colon are intraperitoneal.[xiii] This is important as it affects which organs can be easily accessed during surgery, such as a laparotomy.

In terms of diameter, the cecum is the widest, averaging slightly less than 9 cm in salubrious individuals, and the transverse colon averages less than half dozen cm in diameter.[xiv] The descending and sigmoid colon are slightly smaller, with the sigmoid colon averaging iv–5 cm (i.half dozen–2.0 in) in diameter.[xiv] [xv] Diameters larger than certain thresholds for each colonic department can be diagnostic for megacolon.

Cecum and appendix [edit]

The cecum is the get-go department of the large intestine and is involved in digestion, while the appendix which develops embryologically from it, is not involved in digestion and is considered to exist part of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. The function of the appendix is uncertain, but some sources believe that information technology has a part in housing a sample of the gut microbiota, and is able to help to repopulate the colon with microbiota if depleted during the course of an immune reaction. The appendix has as well been shown to have a high concentration of lymphatic cells.

Ascending colon [edit]

The ascending colon is the first of iv main sections of the large intestine. It is continued to the small intestine by a section of bowel called the cecum. The ascending colon runs upwards through the abdominal cavity toward the transverse colon for approximately eight inches (20 cm).

One of the main functions of the colon is to remove the water and other key nutrients from waste textile and recycle it. Every bit the waste product exits the pocket-sized intestine through the ileocecal valve, it will movement into the cecum and then to the ascending colon where this procedure of extraction starts. The waste material is pumped upwards toward the transverse colon by peristalsis. The ascending colon is sometimes fastened to the appendix via Gerlach's valve. In ruminants, the ascending colon is known as the spiral colon.[16] [17] [18] Taking into account all ages and sexes, colon cancer occurs hither most oftentimes (41%).[19]

Transverse colon [edit]

The transverse colon is the part of the colon from the hepatic flexure, also known every bit the right colic, (the turn of the colon past the liver) to the splenic flexure besides known as the left colic, (the turn of the colon by the spleen). The transverse colon hangs off the stomach, attached to information technology by a large fold of peritoneum chosen the greater omentum. On the posterior side, the transverse colon is connected to the posterior abdominal wall by a mesentery known as the transverse mesocolon.

The transverse colon is encased in peritoneum, and is therefore mobile (dissimilar the parts of the colon immediately earlier and after it).

The proximal 2-thirds of the transverse colon is perfused past the heart colic artery, a branch of the superior mesenteric avenue (SMA), while the latter tertiary is supplied by branches of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). The "watershed" area between these ii blood supplies, which represents the embryologic division betwixt the midgut and hindgut, is an surface area sensitive to ischemia.

Descending colon [edit]

The descending colon is the office of the colon from the splenic flexure to the start of the sigmoid colon. One part of the descending colon in the digestive system is to store feces that volition be emptied into the rectum. It is retroperitoneal in two-thirds of humans. In the other third, it has a (normally short) mesentery.[20] The arterial supply comes via the left colic artery. The descending colon is also called the distal gut, equally it is further along the gastrointestinal tract than the proximal gut. Gut flora are very dense in this region.

Sigmoid colon [edit]

The sigmoid colon is the part of the big intestine after the descending colon and earlier the rectum. The name sigmoid means S-shaped (run across sigmoid; cf. sigmoid sinus). The walls of the sigmoid colon are muscular and contract to increase the pressure level within the colon, causing the stool to motility into the rectum.

The sigmoid colon is supplied with blood from several branches (usually between ii and half dozen) of the sigmoid arteries, a branch of the IMA. The IMA terminates every bit the superior rectal artery.

Sigmoidoscopy is a common diagnostic technique used to examine the sigmoid colon.

Rectum [edit]

The rectum is the final section of the large intestine. It holds the formed feces awaiting elimination via defecation. It is nigh 12 cm long.[21]

Appearance [edit]

The cecum – the first part of the large intestine

- Taeniae coli – iii bands of smooth muscle

- Haustra – bulges caused by contraction of taeniae coli

- Epiploic appendages – small fat accumulations on the viscera

The taenia coli run the length of the big intestine. Because the taenia coli are shorter than the big bowel itself, the colon becomes sacculated, forming the haustra of the colon which are the shelf-like intraluminal projections.[22]

Blood supply [edit]

Arterial supply to the colon comes from branches of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). Menstruation betwixt these ii systems communicates via the marginal artery of the colon that runs parallel to the colon for its entire length. Historically, a structure variously identified as the arc of Riolan or meandering mesenteric artery (of Moskowitz) was thought to connect the proximal SMA to the proximal IMA. This variably present construction would be important if either vessel were occluded. However, at to the lowest degree one review of the literature questions the being of this vessel, with some experts calling for the abolitionism of these terms from time to come medical literature.[23]

Venous drainage ordinarily mirrors colonic arterial supply, with the junior mesenteric vein draining into the splenic vein, and the superior mesenteric vein joining the splenic vein to grade the hepatic portal vein that then enters the liver.

Lymphatic drainage [edit]

Lymphatic drainage from the ascending colon and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon is to the ileocolic lymph nodes and the superior mesenteric lymph nodes, which bleed into the cisterna chyli.[24] The lymph from the distal ane-third of the transverse colon, the descending colon, the sigmoid colon, and the upper rectum drain into the inferior mesenteric and colic lymph nodes.[24] The lower rectum to the anal culvert above the pectinate line drain to the internal ileocolic nodes.[25] The anal canal below the pectinate line drains into the superficial inguinal nodes.[25] The pectinate line simply roughly marks this transition.

Nerve supply [edit]

Sympathetic supply: superior & junior mesenteric ganglia; parasympathetic supply: vagus & pelvic fretfulness

Development [edit]

The endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm are germ layers that develop in a process called gastrulation. Gastrulation occurs early on in homo development. The alimentary canal is derived from these layers.[26]

| | This section needs expansion. Yous can help by adding to it. (March 2017) |

Variation [edit]

1 variation on the normal anatomy of the colon occurs when extra loops form, resulting in a colon that is up to five metres longer than normal. This condition, referred to every bit redundant colon, typically has no directly major health consequences, though rarely volvulus occurs, resulting in obstruction and requiring firsthand medical attending.[27] [28] A significant indirect wellness upshot is that use of a standard adult colonoscope is difficult and in some cases impossible when a redundant colon is present, though specialized variants on the instrument (including the pediatric variant) are useful in overcoming this problem.[29]

Microanatomy [edit]

Colonic crypts [edit]

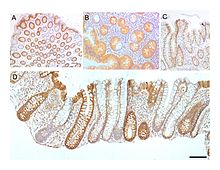

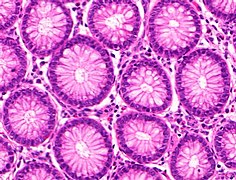

Colonic crypts (intestinal glands) within 4 tissue sections. The cells have been stained to testify a brown-orange color if the cells produce the mitochondrial protein cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (CCOI), and the nuclei of the cells (located at the outer edges of the cells lining the walls of the crypts) are stained blue-gray with haematoxylin. Panels A, B were cut across the long axes of the crypts and panels C, D were cutting parallel to the long axes of the crypts. In panel A the bar shows 100 µm and allows an gauge of the frequency of crypts in the colonic epithelium. Panel B includes iii crypts in cross-section, each with one segment deficient for CCOI expression and at least ane crypt, on the right side, undergoing fission into two crypts. Panel C shows, on the left side, a crypt fissioning into two crypts. Console D shows typical small clusters of two and iii CCOI deficient crypts (the bar shows fifty µm). The images were made from original photomicrographs, but panels A, B and D were also included in an commodity[30] and illustrations were published with Artistic Commons Attribution-Noncommercial License allowing re-employ.

The wall of the large intestine is lined with simple columnar epithelium with invaginations. The invaginations are called the abdominal glands or colonic crypts.

-

Micrograph of normal big instestinal crypts.

-

Anatomy of normal big intestinal crypts

The colon crypts are shaped like microscopic thick walled test tubes with a primal hole downward the length of the tube (the crypt lumen). Iv tissue sections are shown here, two cut beyond the long axes of the crypts and two cut parallel to the long axes. In these images the cells have been stained past immunohistochemistry to show a brownish-orange color if the cells produce a mitochondrial poly peptide chosen cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (CCOI). The nuclei of the cells (located at the outer edges of the cells lining the walls of the crypts) are stained bluish-greyness with haematoxylin. As seen in panels C and D, crypts are nearly 75 to about 110 cells long. Baker et al.[31] constitute that the average crypt circumference is 23 cells. Thus, past the images shown hither, in that location are an average of well-nigh 1,725 to 2,530 cells per colonic crypt. Nooteboom et al.[32] measuring the number of cells in a minor number of crypts reported a range of one,500 to iv,900 cells per colonic crypt. Cells are produced at the crypt base of operations and drift upward along the crypt axis earlier being shed into the colonic lumen days later on.[31] There are five to half-dozen stem cells at the bases of the crypts.[31]

As estimated from the image in console A, there are nearly 100 colonic crypts per foursquare millimeter of the colonic epithelium.[33] Since the boilerplate length of the human colon is 160.5 cm[11] and the average inner circumference of the colon is half-dozen.2 cm,[33] the inner surface epithelial area of the human colon has an average area of about 995 cm2, which includes 9,950,000 (close to 10 1000000) crypts.

In the four tissue sections shown hither, many of the intestinal glands take cells with a mitochondrial Deoxyribonucleic acid mutation in the CCOI gene and appear mostly white, with their main colour beingness the blue-gray staining of the nuclei. As seen in panel B, a portion of the stem cells of three crypts appear to have a mutation in CCOI, and so that 40% to l% of the cells arising from those stalk cells class a white segment in the cross cut area.

Overall, the percent of crypts deficient for CCOI is less than 1% before age xl, but then increases linearly with historic period.[30] Colonic crypts scarce for CCOI in women reaches, on boilerplate, 18% in women and 23% in men by 80–84 years of age.[xxx]

Crypts of the colon can reproduce by fission, as seen in panel C, where a crypt is fissioning to class two crypts, and in panel B where at to the lowest degree one catacomb appears to be fissioning. Nearly crypts deficient in CCOI are in clusters of crypts (clones of crypts) with ii or more CCOI-scarce crypts adjacent to each other (come across console D).[30]

Mucosa [edit]

About 150 of the many thousands of protein coding genes expressed in the large intestine, some are specific to the mucous membrane in unlike regions and include CEACAM7.[34]

Function [edit]

The large intestine absorbs water and any remaining absorbable nutrients from the food before sending the indigestible matter to the rectum. The colon absorbs vitamins that are created by the colonic bacteria, such equally thiamine, riboflavin, and vitamin M (especially important as the daily ingestion of vitamin K is not usually enough to maintain adequate blood coagulation).[35] [ commendation needed ] [36] Information technology also compacts carrion, and stores fecal affair in the rectum until it can be discharged via the anus in defecation.

The big intestine also secretes K+ and Cl-. Chloride secretion increases in cystic fibrosis. Recycling of various nutrients takes identify in the colon. Examples include fermentation of carbohydrates, brusque chain fatty acids, and urea cycling.[37] [ commendation needed ]

The appendix contains a small amount of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue which gives the appendix an undetermined role in amnesty. However, the appendix is known to exist important in fetal life as it contains endocrine cells that release biogenic amines and peptide hormones important for homeostasis during early growth and development.[38]

By the time the chyme has reached this tube, about nutrients and 90% of the h2o take been absorbed by the body. At this signal some electrolytes like sodium, magnesium, and chloride are left as well as boxy parts of ingested food (e.thou., a large part of ingested amylose, starch which has been shielded from digestion heretofore, and dietary fiber, which is largely boxy carbohydrate in either soluble or insoluble form). As the chyme moves through the large intestine, nearly of the remaining water is removed, while the chyme is mixed with mucus and leaner (known equally gut flora), and becomes carrion. The ascending colon receives fecal material as a liquid. The muscles of the colon then motility the watery waste product material forward and slowly absorb all the backlog water, causing the stools to gradually solidify as they move forth into the descending colon.[39]

The bacteria suspension down some of the fiber for their own nourishment and create acetate, propionate, and butyrate as waste matter products, which in plow are used by the prison cell lining of the colon for nourishment.[40] No poly peptide is made available. In humans, perhaps 10% of the undigested saccharide thus becomes available, though this may vary with diet;[41] in other animals, including other apes and primates, who have proportionally larger colons, more is made bachelor, thus permitting a higher portion of plant fabric in the diet. The large intestine[42] produces no digestive enzymes — chemical digestion is completed in the minor intestine before the chyme reaches the big intestine. The pH in the colon varies between 5.five and 7 (slightly acidic to neutral).[43]

Standing slope osmosis [edit]

Water absorption at the colon typically proceeds against a transmucosal osmotic force per unit area slope. The continuing gradient osmosis is the reabsorption of h2o against the osmotic gradient in the intestines. Cells occupying the abdominal lining pump sodium ions into the intercellular infinite, raising the osmolarity of the intercellular fluid. This hypertonic fluid creates an osmotic pressure that drives water into the lateral intercellular spaces by osmosis via tight junctions and adjacent cells, which so in turn moves across the basement membrane and into the capillaries, while more than sodium ions are pumped again into the intercellular fluid.[44] Although water travels down an osmotic gradient in each private step, overall, h2o usually travels against the osmotic gradient due to the pumping of sodium ions into the intercellular fluid. This allows the large intestine to absorb water despite the blood in capillaries being hypotonic compared to the fluid within the intestinal lumen.

Gut flora [edit]

The large intestine houses over 700 species of bacteria that perform a variety of functions, as well equally fungi, protozoa, and archaea. Species diversity varies by geography and diet.[45] The microbes in a human distal gut frequently number in the vicinity of 100 trillion, and tin can weigh effectually 200 grams (0.44 pounds). This mass of generally symbiotic microbes has recently been chosen the latest human organ to be "discovered" or in other words, the "forgotten organ".[46]

The large intestine absorbs some of the products formed past the leaner inhabiting this region. Undigested polysaccharides (cobweb) are metabolized to short-chain fatty acids by bacteria in the big intestine and absorbed by passive improvidence. The bicarbonate that the big intestine secretes helps to neutralize the increased acidity resulting from the formation of these fat acids.[47]

These bacteria too produce large amounts of vitamins, especially vitamin K and biotin (a B vitamin), for absorption into the blood. Although this source of vitamins, in general, provides only a small function of the daily requirement, it makes a meaning contribution when dietary vitamin intake is low. An private who depends on absorption of vitamins formed by leaner in the large intestine may become vitamin-deficient if treated with antibiotics that inhibit the vitamin producing species of bacteria too as the intended affliction-causing bacteria.[48]

Other bacterial products include gas (flatus), which is a mixture of nitrogen and carbon dioxide, with small amounts of the gases hydrogen, marsh gas, and hydrogen sulfide. Bacterial fermentation of undigested polysaccharides produces these. Some of the fecal aroma is due to indoles, metabolized from the amino acrid tryptophan. The normal flora is too essential in the development of certain tissues, including the cecum and lymphatics.[ citation needed ]

They are likewise involved in the product of cross-reactive antibodies. These are antibodies produced by the immune system against the normal flora, that are likewise effective confronting related pathogens, thereby preventing infection or invasion.

The two most prevalent phyla of the colon are Bacillota and Bacteroidota. The ratio between the two seems to vary widely equally reported by the Man Microbiome Project.[49] Bacteroides are implicated in the initiation of colitis and colon cancer. Bifidobacteria are also abundant, and are oftentimes described equally 'friendly leaner'.[50] [51]

A mucus layer protects the big intestine from attacks from colonic commensal bacteria.[52]

Clinical significance [edit]

Disease [edit]

Post-obit are the near common diseases or disorders of the colon:

- Angiodysplasia of the colon

- Appendicitis

- Chronic functional abdominal pain

- Colitis

- Colorectal cancer

- Colorectal polyp

- Constipation

- Crohn's disease

- Diarrhea

- Diverticulitis

- Diverticulosis

- Hirschsprung's disease (aganglionosis)

- Ileus

- Intussusception

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Pseudomembranous colitis

- Ulcerative colitis and toxic megacolon

Colonoscopy [edit]

Colonoscopy is the endoscopic examination of the large intestine and the distal part of the small bowel with a CCD photographic camera or a fiber optic camera on a flexible tube passed through the anus. It tin can provide a visual diagnosis (east.g. ulceration, polyps) and grants the opportunity for biopsy or removal of suspected colorectal cancer lesions. Colonoscopy can remove polyps as pocket-size as one millimetre or less. One time polyps are removed, they can exist studied with the aid of a microscope to determine if they are precancerous or not. It takes 15 years or less for a polyp to plough cancerous.

Colonoscopy is like to sigmoidoscopy—the deviation being related to which parts of the colon each can examine. A colonoscopy allows an examination of the entire colon (1200–1500 mm in length). A sigmoidoscopy allows an examination of the distal portion (about 600 mm) of the colon, which may exist sufficient because benefits to cancer survival of colonoscopy have been limited to the detection of lesions in the distal portion of the colon.[53] [54] [55]

A sigmoidoscopy is often used as a screening procedure for a full colonoscopy, oftentimes done in conjunction with a stool-based test such as a fecal occult claret test (FOBT), fecal immunochemical examination (FIT), or multi-target stool Deoxyribonucleic acid examination (Cologuard) or blood-based test, SEPT9 DNA methylation examination (Epi proColon).[56] About 5% of these screened patients are referred to colonoscopy.[57]

Virtual colonoscopy, which uses 2D and 3D imagery reconstructed from computed tomography (CT) scans or from nuclear magnetic resonance (MR) scans, is also possible, as a totally non-invasive medical examination, although it is not standard and however under investigation regarding its diagnostic abilities. Furthermore, virtual colonoscopy does non let for therapeutic maneuvers such as polyp/tumour removal or biopsy nor visualization of lesions smaller than five millimeters. If a growth or polyp is detected using CT colonography, a standard colonoscopy would however need to exist performed. Additionally, surgeons take lately been using the term pouchoscopy to refer to a colonoscopy of the ileo-anal pouch.

Other animals [edit]

The large intestine is truly singled-out only in tetrapods, in which information technology is about ever separated from the small-scale intestine past an ileocaecal valve. In well-nigh vertebrates, however, it is a relatively brusque structure running directly to the anus, although noticeably wider than the small intestine. Although the caecum is nowadays in most amniotes, only in mammals does the remainder of the big intestine develop into a true colon.[58]

In some small mammals, the colon is straight, as information technology is in other tetrapods, merely, in the majority of mammalian species, it is divided into ascending and descending portions; a distinct transverse colon is typically present only in primates. However, the taeniae coli and accompanying haustra are not found in either carnivorans or ruminants. The rectum of mammals (other than monotremes) is derived from the cloaca of other vertebrates, and is, therefore, not truly homologous with the "rectum" institute in these species.[58]

In fish, in that location is no true big intestine, but but a short rectum connecting the end of the digestive part of the gut to the cloaca. In sharks, this includes a rectal gland that secretes common salt to help the fauna maintain osmotic balance with the seawater. The gland somewhat resembles a caecum in construction simply is not a homologous structure.[58]

Additional images [edit]

-

Intestines

-

Colon. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

See also [edit]

- Large intestine (Chinese medicine)

- Colectomy

- Colonic ulcer

References [edit]

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1177 of the 20th edition of Gray'south Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1177 of the 20th edition of Gray'south Anatomy (1918)

- ^ a b c "large intestine". NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Wellness. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2014-03-04 .

- ^ Kapoor, Vinay Kumar (xiii Jul 2011). Gest, Thomas R. (ed.). "Large Intestine Anatomy". Medscape. WebMD LLC. Retrieved 2013-08-20 .

- ^ Gray, Henry (1918). Gray's Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

- ^ "large intestine". Mosby's Medical Lexicon (8th ed.). Elsevier. 2009. ISBN9780323052900.

- ^ "intestine". Concise Medical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2010. ISBN9780199557141.

- ^ "big intestine". A Dictionary of Biology. Oxford University Press. 2013. ISBN9780199204625.

- ^ "Large intestine". Archived from the original on 2015-08-28. Retrieved 2016-07-24 .

- ^ Drake, R.Fifty.; Vogl, W.; Mitchell, A.W.M. (2010). Greyness'south Anatomy for Students. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone.

- ^ Azzouz, Laura; Sharma, Sandeep (2020). "Physiology, Large Intestine". NCBI Bookshelf. PMID 29939634.

- ^ David Krogh (2010), Biological science: A Guide to the Natural World, Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Visitor, p. 597, ISBN978-0-321-61655-5

- ^ a b Hounnou G, Destrieux C, Desmé J, Bertrand P, Velut South (2002). "Anatomical study of the length of the human intestine". Surg Radiol Anat. 24 (5): 290–iv. doi:x.1007/s00276-002-0057-y. PMID 12497219. S2CID 33366428.

- ^ "Peritoneum". Mananatomy.com. 2013-01-18. Archived from the original on 2018-10-08. Retrieved 2013-02-07 .

- ^ "Untitled".

- ^ a b Horton, 1000. M.; Corl, F. M.; Fishman, Eastward. K. (March 2000). "CT evaluation of the colon: inflammatory disease". Radiographics. 20 (2): 399–418. doi:10.1148/radiographics.20.2.g00mc15399. ISSN 0271-5333. PMID 10715339.

- ^ Rossini, Francesco Paolo (1975), "The normal colon", in Rossini, Francesco Paolo (ed.), Atlas of coloscopy, Springer New York, pp. 46–55, doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-9650-9_12, ISBN9781461596509

- ^ Medical dictionary

- ^ Spiral colon and caecum, archived from the original on 2016-03-04, retrieved 2014-04-02

- ^ "Answers – The Most Trusted Identify for Answering Life's Questions". Answers.com.

- ^ Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RG, Barzi A, Jemal A (March 1, 2017). "Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017". CA Cancer J. Clin. 67 (3): 177–193. doi:ten.3322/caac.21395. PMID 28248415.

- ^ Smithivas, T.; Hyams, P. J.; Rahal, J. J. (1971-12-01). "Gentamicin and ampicillin in human bile". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 124 Suppl: S106–108. doi:ten.1093/infdis/124.supplement_1.s106. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 5126238.

- ^ "Beefcake of Colon and Rectum | SEER Training". training.seer.cancer.gov . Retrieved 2021-04-14 .

- ^ Anatomy at a Glance by Omar Faiz and David Moffat

- ^ Lange, Johan F.; Komen, Niels; Akkerman, Germaine; Nout, Erik; Horstmanshoff, Herman; Schlesinger, Frans; Bonjer, Jaap; Kleinrensink, Gerrit-Jan (June 2007). "Riolan'southward arch: confusing, misnomer, and obsolete. A literature survey of the connectedness(due south) between the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries". Am J Surg. 193 (6): 742–748. doi:x.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.10.022. PMID 17512289.

- ^ a b Snell, Richard S. (1992). Clinical Beefcake for Medical Students (4 ed.). Boston: Little, Dark-brown, and Company. pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b Le, Tao; et al. (2014). First Aid for the USMLE Pace 1. McGraw-Hill Teaching. p. 196.

- ^ Wilson, Danielle J.; Bordoni, Bruno (2022), "Embryology, Bowel", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31424831, retrieved 2022-05-27

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (2006-10-13). "Redundant colon: A health business organization?". Ask a Digestive System Specialist. MayoClinic.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-06-11 .

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff. "Redundant colon: A health business organisation? (To a higher place with active paradigm links)". riversideonline.com . Retrieved 8 Nov 2013.

- ^ Lichtenstein, Gary R.; Peter D. Park; William B. Long; Gregory M. Ginsberg; Michael L. Kochman (18 August 1998). "Use of a Push Enteroscope Improves Ability to Perform Total Colonoscopy in Previously Unsuccessful Attempts at Colonoscopy in Adult Patients". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 94 (1): 187–90. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00794.10. PMID 9934753. S2CID 24536782. Note: single utilize PDF copy provided complimentary by Blackwell Publishing for purposes of Wikipedia content enrichment.

- ^ a b c d Bernstein C, Facista A, Nguyen H, Zaitlin B, Hassounah N, Loustaunau C, Payne CM, Banerjee B, Goldschmid S, Tsikitis VL, Krouse R, Bernstein H (2010). "Cancer and historic period related colonic crypt deficiencies in cytochrome c oxidase I". World J Gastrointest Oncol. two (12): 429–42. doi:ten.4251/wjgo.v2.i12.429. PMC3011097. PMID 21191537.

- ^ a b c Baker AM, Cereser B, Melton S, Fletcher AG, Rodriguez-Justo Yard, Tadrous PJ, Humphries A, Elia Grand, McDonald SA, Wright NA, Simons BD, Jansen M, Graham TA (2014). "Quantification of crypt and stalk cell development in the normal and neoplastic homo colon". Cell Rep. 8 (4): 940–7. doi:x.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.019. PMC4471679. PMID 25127143.

- ^ Nooteboom M, Johnson R, Taylor RW, Wright NA, Lightowlers RN, Kirkwood TB, Mathers JC, Turnbull DM, Greaves LC (2010). "Age-associated mitochondrial DNA mutations lead to pocket-size but significant changes in cell proliferation and apoptosis in human being colonic crypts". Aging Cell. 9 (1): 96–nine. doi:10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00531.x. PMC2816353. PMID 19878146.

- ^ a b Nguyen H, Loustaunau C, Facista A, Ramsey L, Hassounah N, Taylor H, Krouse R, Payne CM, Tsikitis VL, Goldschmid S, Banerjee B, Perini RF, Bernstein C (2010). "Deficient Pms2, ERCC1, Ku86, CcOI in field defects during progression to colon cancer". J Vis Exp (41). doi:10.3791/1931. PMC3149991. PMID 20689513.

- ^ Gremel, Gabriela; Wanders, Alkwin; Cedernaes, Jonathan; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn; Edlund, Karolina; Sjöstedt, Evelina; Uhlén, Mathias; Pontén, Fredrik (2015-01-01). "The human alimentary canal-specific transcriptome and proteome as divers by RNA sequencing and antibody-based profiling". Periodical of Gastroenterology. fifty (1): 46–57. doi:10.1007/s00535-014-0958-vii. ISSN 0944-1174. PMID 24789573. S2CID 21302849.

- ^ Sellers, Rani South.; Morton, Daniel (2014). "The Colon: From Banal to Brilliant". Toxicologic Pathology. 42 (1): 67–81. doi:x.1177/0192623313505930. ISSN 0192-6233. PMID 24129758. S2CID 20465985 – via Web of Science.

- ^ Booth, Sarah (Apr 2012). "Vitamin Thou: Nutrient Consumption and Dietary Intakes". Nutrient Nutrition Enquiry. 56. doi:10.3402/fnr.v56i0.5505. PMC3321250. PMID 22489217.

- ^ "The Large Intestine (Human)". News-Medical.net. 2009-eleven-17. Retrieved 2017-03-xv .

- ^ Martin, Loren G. (1999-x-21). "What is the role of the human appendix? Did it once have a purpose that has since been lost?". Scientific American . Retrieved 2014-03-03 .

- ^ La función de la hidroterapia de colon Retrieved on 2010-01-21

- ^ Terry L. Miller; Meyer J. Wolin (1996). "Pathways of Acetate, Propionate, and Butyrate Formation by the Human Fecal Microbial Flora". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 62 (5): 1589–1592. Bibcode:1996ApEnM..62.1589M. doi:x.1128/AEM.62.5.1589-1592.1996. PMC167932. PMID 8633856.

- ^ McNeil, NI (1984). "The contribution of the big intestine to free energy supplies in man". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 39 (2): 338–342. doi:10.1093/ajcn/39.ii.338. PMID 6320630.

- ^ lorriben (2016-07-09). "What Side is Your Appendix Located – Maglenia". Maglenia. Archived from the original on 2016-ten-09. Retrieved 2016-10-23 .

- ^ Function Of The Large Intestine Archived 2013-eleven-05 at the Wayback Automobile Retrieved on 2010-01-21

- ^ "Absorption of Water and Electrolytes".

- ^ Yatsunenko, Tanya; et al. (2012). "Man gut microbiome viewed across historic period and geography". Nature. 486 (7402): 222–227. Bibcode:2012Natur.486..222Y. doi:x.1038/nature11053. PMC3376388. PMID 22699611.

- ^ O'Hara, Ann K.; Shanahan, Fergus (2006). "The gut flora as a forgotten organ". EMBO Reports. seven (vii): 688–693. doi:ten.1038/sj.embor.7400731. PMC1500832. PMID 16819463.

- ^ den Besten, Gijs; van Eunen, Karen; Groen, Albert One thousand.; Venema, Koen; Reijngoud, Dirk-January; Bakker, Barbara G. (2013-09-01). "The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay betwixt diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism". Periodical of Lipid Research. 54 (ix): 2325–2340. doi:10.1194/jlr.R036012. ISSN 0022-2275. PMC3735932. PMID 23821742.

- ^ Murdoch, Travis B.; Detsky, Allan S. (2012-12-01). "Time to Recognize Our Fellow Travellers". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 27 (12): 1704–1706. doi:ten.1007/s11606-012-2105-half dozen. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC3509308. PMID 22588826.

- ^ Homo Microbiome Project Consortium (Jun 14, 2012). "Structure, function and multifariousness of the healthy homo microbiome". Nature. 486 (7402): 207–214. Bibcode:2012Natur.486..207T. doi:10.1038/nature11234. PMC3564958. PMID 22699609.

- ^ Bloom, Seth M.; Bijanki, Vinieth North.; Nava, Gerardo M.; Sun, Lulu; Malvin, Nicole P.; Donermeyer, David L.; Dunne, West. Michael; Allen, Paul M.; Stappenbeck, Thaddeus Due south. (2011-05-19). "Commensal Bacteroides species induce colitis in host-genotype-specific fashion in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease". Cell Host & Microbe. ix (5): 390–403. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.009. ISSN 1931-3128. PMC3241010. PMID 21575910.

- ^ Bottacini, Francesca; Ventura, Marco; van Sinderen, Douwe; O'Connell Motherway, Mary (2014-08-29). "Multifariousness, ecology and intestinal part of bifidobacteria". Microbial Cell Factories. xiii (Suppl 1): S4. doi:10.1186/1475-2859-13-S1-S4. ISSN 1475-2859. PMC4155821. PMID 25186128.

- ^ Johansson, Malin Eastward.5.; Sjövall, Henrik; Hansson, Gunnar C. (2013-06-01). "The gastrointestinal mucus system in wellness and disease". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 10 (6): 352–361. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2013.35. ISSN 1759-5045. PMC3758667. PMID 23478383.

- ^ Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L (January 2009). "Clan of colonoscopy and decease from colorectal cancer". Ann. Intern. Med. 150 (1): 1–8. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-i-200901060-00306. PMID 19075198. equally PDF Archived 2012-01-eighteen at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Singh H, Nugent Z, Mahmud SM, Demers AA, Bernstein CN (March 2010). "Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published studies". Am J Gastroenterol. 105 (3): 663–673. doi:ten.1038/ajg.2009.650. PMID 19904239. S2CID 11145247.

- ^ Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Alterhofen L, Haug U (January 2010). "Protection from right- and left-sided colorectal neoplasms subsequently colonoscopy: population-based study". J Natl Cancer Inst. 102 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1093/jnci/djp436. PMID 20042716. S2CID 1887714.

- ^ Tepus, M; Yau, TO (20 May 2020). "Non-Invasive Colorectal Cancer Screening: An Overview". Gastrointestinal Tumors. vii (3): 62–73. doi:10.1159/000507701. PMC7445682. PMID 32903904.

- ^ Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, et al. (May 2010). "In one case-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 375 (9726): 1624–33. doi:ten.1016/S0140-6736(10)60551-X. PMID 20430429. S2CID 15194212. equally PDF Archived 2012-03-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas Southward. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 351–354. ISBN978-0-03-910284-5.

External links [edit]

- 09-118h. at Merck Transmission of Diagnosis and Therapy Habitation Edition

Another Name For Large Intestine,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Large_intestine

Posted by: williamswict2001.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Another Name For Large Intestine"

Post a Comment